History of Buses in Public Transportation

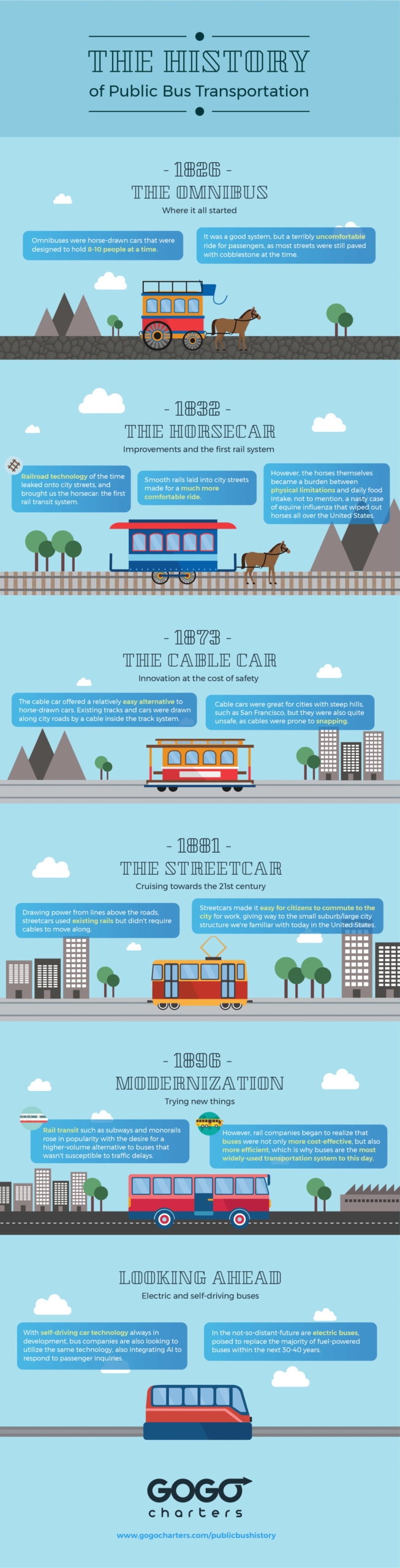

Did you know that public transportation has existed, in some form, since the 1820s? It all began with a simple system of horse-drawn carriages that, surprisingly, took a while to catch on. But once it did, public transportation would quickly progress from simple horsecars to cable cars, rail lines, and finally, the modern buses we know today—all while putting a little extra influence on how we think about city planning.

We might be a little biased, but we think the history of buses is pretty fascinating. Keep reading to learn for yourself!

Quick Navigation

- The First Failed Public Bus Attempt

- The Omnibus

- The Horsecar

- The Cable Car

- The Streetcar

- Rapid Transit

- Bus Transit Today

- Electric & Self-Driving Buses

- Sources

The First Failed Public Bus Attempt

The first person to propose the idea of a public transportation system was Blaise Pascal, who launched a handful of horse-drawn carriage routes in Paris in 1662. Known as “Five-Penny Coaches,” or “Carosses à Cinq Sous,” the carriages were initially a hit, but it only took about ten years for the hype to completely die off. And, since they were only available to the nobility and the gentry, many “commoners” didn’t even get the chance to see if they liked the service.

And thus, the first public transportation system was a flop. It would be 150 years before someone finally got the idea to catch on for good.

The Omnibus

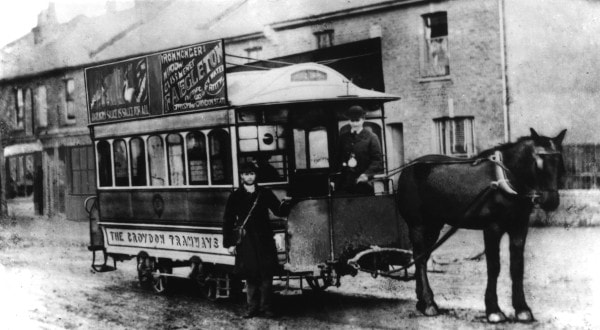

Even in their earliest days, buses were used as rolling advertisements. Image source: Museum of Croydon, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

A century-and-a-half and a lot of sore feet later, the year 1826 brought us the Omnibus, the first land-based innovation in public transportation (public ferry boats had been commonplace since the early 1800s).

Omnibuses were horse-drawn passenger wagons that were pulled by one to three horses, depending on their size. The largest models held up to 42 passengers, and some even featured two stories with an open top!

It was France who, again, tested this public transportation system—this time-saving room for those without blue blood. The idea stuck, and even made its way across the pond to New York City, who had established their own omnibus line by 1828. Soon after, many U.S. and European cities followed suit.

This new omnibus system wasn’t without its downsides, though. People generally considered public transportation to be a good thing, but riding on said public transportation wasn’t really a comfortable experience. Cobblestone roads made for a bumpy ride, which was further emphasized by the lack of padding on the seats. Plus, at a price of 12 cents per ride, the omnibus was still a little too expensive for many urban citizens.

With time, though, the system found a middle-class audience who couldn’t afford private stagecoaches but were willing to pay to avoid walking. This audience helped the omnibus stick around long enough to start seeing some improvements.

The Horsecar and the First Rail System

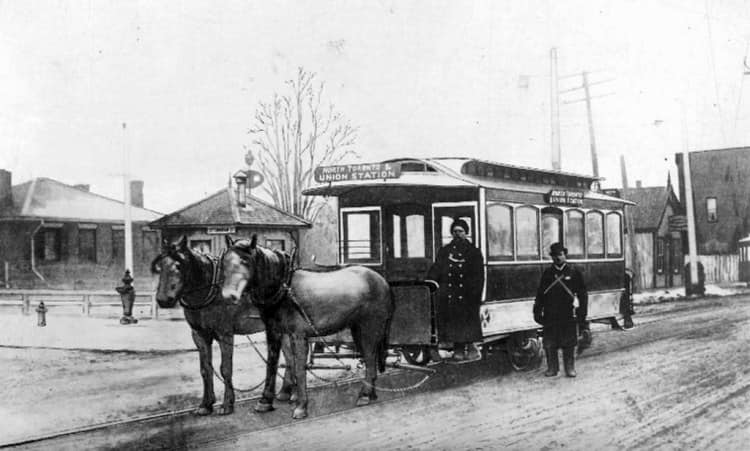

Bumpy, uncomfortable omnibus rides finally became a thing of the past in the 1830s. Cities began laying smooth rails into the streets over pre-existing Omnibus routes, creating the first rail-based transit systems. The rails helped reduce friction on the wheels which made it easier for horses to pull more weight on their vehicles and, of course, made rides much more comfortable.

Now, cars were accommodating three times as many passengers as omnibuses, and lower operating costs reduced the price to 5 cents per ride—making the horsecars accessible to a wider range of citizens. With rides that were both affordable and comfortable, passengers suddenly didn’t mind having to travel further distances across their cities.

A two-horse car in Toronto, circa 1889. Image source: Alfred Pearson, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

With this ease of travel came rapid urbanization, expanded development along the fringes of major cities, and America’s new status as a forerunner of the Industrial Revolution. By the 1880s, more than 30,000 miles of street railways had been laid in the U.S. alone, accommodating over 20,000 horsecars.

But horsecars certainly weren’t without their drawbacks.

Horses could only work for about a two-hour stretch before becoming exhausted, so transit companies had to keep 8-10 horses on hand just to operate one car. An equine influenza outbreak in 1872 wiped out thousands of horses and prevented many commuters from traveling in a timely manner. A lack of regulation on who had the right-of-way caused a lot of traffic jams. Horses ate their weight in food every day, which was a financial burden on companies. And do we even need to mention the manure on the streets?

Public transportation was here to stay, but one thing was clear: it was time to move away from its dependence on animals.

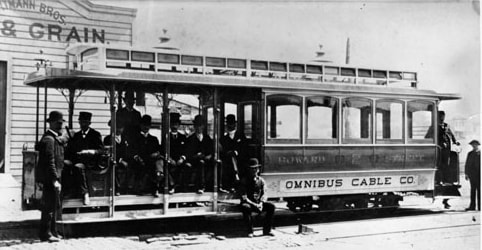

The Cable Car: Innovation at the Cost of Safety

Next up on our public transportation evolution is the cable car, an icon of transit in the United States.

The idea for the cable car was conceived in San Francisco after a bystander, Andrew Smith Hallidie, witnessed a horsecar driver repeatedly whip a horse while the horse struggled to climb up a slippery hill. And in a city that’s notorious for its rolling hills, there was no doubt that other horses were also having difficulties. Plus, some San Francisco hills were simply too steep for horses to climb, no matter how hard they tried.

In 1873, Hallidie invented a new cable-driven system that would eliminate the need for animals in public transportation. The new cable cars ran on existing horsecar rails with one modification: a moving cable between the two rails. Cars had clamps on the bottom that let them hold onto the cables when it was time to move and slowly release the cables when they had to stop.

A modern cable car and railway in San Francisco, California. The cable car is the most iconic form of public transportation in the United States.

This innovation set the stage for animal-free transportation, but unfortunately, cable cars were quite unsafe. Cables were prone to snapping, and dangerous accidents throughout San Francisco’s streets were not uncommon.

Cable cars quickly went out of service, though some still exist today for nostalgia’s

The Streetcar: Transitioning to 21st-Century Buses

The year 1881 brought us the streetcar, a new development in electric-powered and rail-based transportation. Streetcars were powered by cables, which carried electric current, that were strung over their routes. Electric current was carried to the cars via an arm-like extension, and the metal wheels and metal tracks acted as “grounding” for the electrical circuit so that passengers wouldn’t be electrocuted by the car.

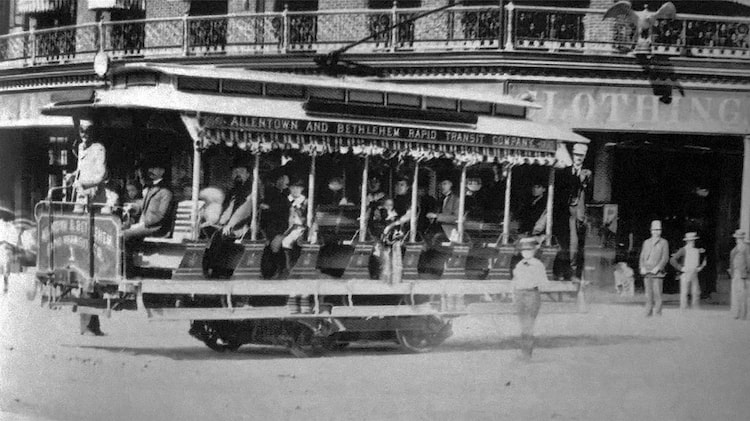

Streetcars, also called trams, trolleys, or electric streetcars, were revolutionary for their time. This car was photographed in Allentown, Pennsylvania. Image source: Self-Scanned, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Making the switch was simple: the rail lines already existed, and most cities simply used old horsecars with new arm attachments. Soon, new streetcar lines popped up and cities began to sprawl even further.

This sprawl began a new era of city planning, where “walkability” was no longer a key feature and residential developments and downtown shopping centers overlapped less frequently. The invention of the streetcar gave way to the sprawling, bustling metropolises we know today: dense commercial areas in the city center with less-dense residential zones surrounding the city.

And since streetcar lines often ran directly into a city’s center, these areas became prime real estate locations for luxury retail chains, million-dollar businesses, and other places that realized they could provide entertainment to a much wider audience with a transportation hub right outside of their front door.

While horse-drawn carriages could only carry passengers across a few blocks, electric streetcars could cover many miles, stretching public transportation access outward and into areas that would eventually develop into city suburbs, known then as “streetcar suburbs.” These small towns preserved the dense, walkable layouts of the cities of old but also housed a single rail line into the nearest major city for easy access to the shopping, dining, and entertainment options of the “big city.”

Streetcars were a hit and a major improvement over previous public transportation services. But two major events were about to take their toll on the world and make it difficult for riders and transit companies alike. The Great Depression caused widespread line closures in the 1930s, and World War II’s strict rations on rubber tires and gasoline sealed the fate of many other already-failing lines.

Still, some streetcar lines remained open, while others converted to bus lines (which we’ll talk about soon). But first, let’s talk about rapid transit, which was already catching on in some cities.

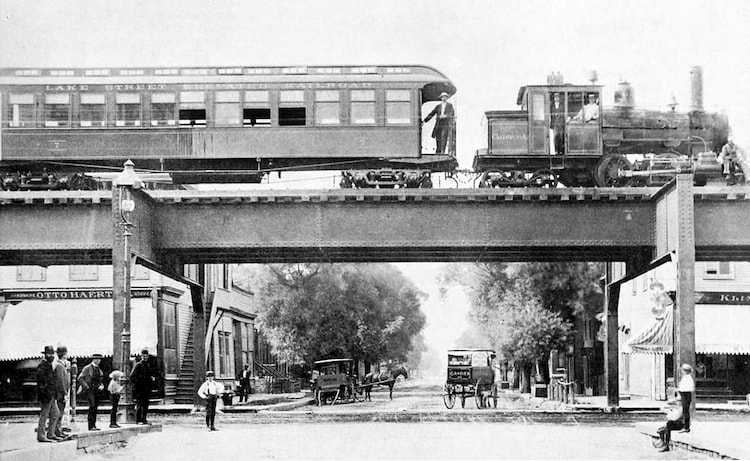

Rapid Transit: Worth the Money?

The appeal for a rapid transit system goes back to the late 19th century, when streetcars were still becoming commonplace. Even though streetcars provided a convenient way to get into and out of a city, they were still victim to some traffic limitations. Thus, “heavy-rail” transit systems (as opposed to “light-rail” streetcar lines) started to spring up in major US cities. Heavy rail would carry trains across long distances without crossing traffic.

In 1892, Chicago was the first city in the United States to develop a rapid-transit system with the opening of the “L” train, which sits elevated above city streets and still runs to this day. Boston followed shortly after in 1897 with the US’s first subway system, which could run freely without the influence of Boston’s harsh winter blizzard conditions and narrow, winding streets.

The 1950s brought us a handful of futuristic monorail systems, namely the short-lived “Trailblazer” monorail in Houston, Texas, which was opened and decommissioned within a matter of months. Seattle constructed a monorail system for the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair but retired the system and declared it a historical landmark in 2003.

Monorails and other heavy- and light-rail systems certainly have their advantages. They’re speedy, they don’t have to navigate traffic jams, and let’s be honest—monorails look really cool. But there are many instances in which a rail system can be inconvenient. Any minor change to a route necessitates a new rail line, which has to be laid into the street while another line is torn out of the street. Regular maintenance could shut down an entire rail line, since there’s often only one train servicing a route. And it can be difficult to justify the massive up-front cost of building rail infrastructure in a new area.

Meanwhile, buses can change routes at a moment’s notice based on the demand of the riders. Transit companies can send one bus to service a route while another is in the shop. And buses don’t require new infrastructure to operate. Unless a city has the budget and the demand for a set-in-stone rail line, a bus system is the more economical choice.

The rail systems of the early 20th century peaked in popularity around 1910, but by 1930, over 230 rail companies had either gone out of business or converted to buses. Studies show that rail systems are only efficient in extremely densely-packed cities, which explains their presence today in major cities such as New York, London, and Hong Kong. Otherwise, cities tend to rely on buses to transport the majority of their citizens.

Bus Transit Today

An articulated bus owned by the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority, or MARTA, in Atlanta, Georgia. Image Source: Kristain Baty from Atlanta,GA, United States, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Mass transit ridership has declined significantly over the last 100 years—so much so that some claim its existence is largely due to tradition rather than necessity. As a car-centric culture began to emerge mid-century, it became commonplace for households to own at least one car. There was a slight pushback to this new normal in the 1960s and 1970s, with environmental concerns in most riders’ minds, but the cars won.

However, there’s still plenty of need for reliable public transportation, particularly in major cities with limited parking and a high cost of living. Owning an automobile isn’t always financially feasible, and public transportation offers a low-cost way to get to school or work.

Knowing what an advantage it can be, many bus companies are working to make public buses more appealing, more affordable for city transit operators, and more environmentally friendly—which brings us to the next stop on our journey.

Looking Ahead: Electric and Self-Driving Buses

With electric buses gaining popularity, many public transportation systems are looking to adopt these environmentally-friendly vehicles to help reduce emissions and keep city air clean. In 2020, Los Angeles announced a plan to add 155 electric buses to the city’s fleet. Meanwhile, New York City, Seattle, and the state of California have made pledges to transition to zero-emission fleets. If all goes according to plan, 33% of all transit buses in the United States will be electric by the year 2045.

But with all of the environmental benefits of electric buses, they can have their drawbacks. “Range anxiety” refers to the fear that a charge won’t hold until a route is completed or a destination is reached. Electric buses can also cost up to $300,000 more than traditional diesel-powered models, deterring many cities from making the switch.

A zero-emission Proterra bus in Detroit, Michigan. Image Source: 42-BRT, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Proterra, a manufacturer known for its battery-powered electric buses, works to address the “range anxiety” felt by many bus transit providers. Charging ports are standard at every bus depot so that drivers can plug buses in after a long day of driving, but Proterra also adds on-route charging stations that can charge a bus in as little as five minutes, ensuring 24-hour service with little to no anxiety.

And while the up-front cost can be intimidating, the lack of fuel costs for electric buses quickly makes up for the initial cost. All things considered, it’s about 2.5 times cheaper to power electric vehicles than it is to power diesel vehicles, and battery prices are expected to drop 50% by 2025, which will help to further reduce the up-front cost.

Perhaps an even more exciting advancement in public transportation options is Olli, a self-driving pod that can either fill in gaps in transit routes or act as an on-demand shuttle service, all while making the roads safer and bringing public transit access to a wider range of riders. Olli has 360-degree vision, cognitive response technology, and a special obstacle avoidance system to keep her passengers safe. Plus, she’s powered by electricity.

Olli has been spotted in National Harbor, Maryland; Turin, Italy; and a handful of other American and European cities. After the big leaps we’ve explored in public transportation through the centuries, we can’t wait to see where this adorable vision of the future takes us.

Sources:

https://www.downsizinggovernment.org/transportation/urban-transit

https://www.wired.com/2008/03/march-18-1662-the-bus-starts-here-in-paris/

http://gizmodo.com/5-cities-with-driverless-public-buses-on-the-streets-ri-1736146699

http://www.cable-car-guy.com/html/cchorse.html

http://www.cablecarmuseum.org/heritage.html

https://new.siemens.com/global/en/company/about/history/news/first-electric-streetcar.html

http://www.bostonstreetcars.com/how-a-streetcar-works.html

https://www.proterra.com/technology/chargers/

https://www.publicpower.org/periodical/article/electric-buses-mass-transit-seen-cost-effective

https://www.eesi.org/papers/view/fact-sheet-electric-buses-benefits-outweigh-costs

Recent Posts

- GOGO Charters Expands to the Midwest: Bringing Luxury Intercity Travel to Chicago and Beyond

- Texans Are All Aboard: The Overwhelming Response to GOGO Charters’ New Line Runs

- GOGO Charters Launches Texas-Wide Luxury Line Run Network: Redefining Regional Travel

- Your Charter Bus Packing and Carry-On Guide

- Average Vacation Costs in 2024: Transportation, Entertainment, and Budgeting Tips

- 20 Best Multigenerational Travel Destinations in the U.S.

- 88 Must-Know Travel Statistics by Age Group for 2024

- Top 25 Affordable Warm Weather Destinations in the U.S. for Winter Travel

Do you need to rent a charter bus?

Do you need a long-term shuttle service?

We offer contracted shuttle services for businesses, schools, hotels, and more. Contact our experts at 1-844-897-5201 to discuss your long-term transportation plans.

Overall Rating: 9.98 out of 10 from 422 unique reviews