Ride to Liberation: A Brief History of Buses in Activism

Group transportation has played an integral role in the mobilization of protests across various historical eras. Mass transportation forms like buses and subways have been both the subjects of protest and the physical catalysts for moving protestors toward social change.

From the 1950s to present day, buses have acted as major battlegrounds regarding racial segregation, ableism, sexism, and transportation accessibility to the impoverished. Public transportation and private buses have been present in various veins of activism, spanning from the monumental era of the Civil Rights Movement to modern-day political movements. Over the years, GOGO Charters has shown support for crucial socio-political demonstrations like March for Our Lives and Women’s Marches. Not only is it important for us to understand the goals and implications of these movements, but we must also understand the history and causes.

Bus Boycotts of the Mid-20th Century

Public buses became a topic of debate as tensions continuously grew over Jim Crow laws and racial segregation. Like most public spaces in this era, African-Americans were separated from white passengers, required to sit in designated seats in the back of the bus. Even if the bus was only partially occupied, black passengers were prohibited from sitting in seats designated for white passengers. Private black-owned bus companies were also illegal during this era, meaning African American passengers were often forced to stand when the back of the bus became crowded.

Although several bus boycotts took place during this era, the Montgomery bus boycott is often deemed among the most influential. Rosa Parks’s arrest in winter of 1955 is typically one of the first occurrences pictured when bus boycotts are discussed.

Though, before Parks and Montgomery, protestors of transportation segregation made their voices heard in Baton Rouge, Louisiana during 1953. With over two-thirds of bus riders being black during this time and bus fares steadily rising, buses had a disproportionate amount of white-designated seats, leaving black passengers often standing over empty seats. Reverend Theodore Jefferson Jemison and other leaders in Baton Rouge’s black community rallied support to reform the city’s bus seating policy.

Reverend Jemison successfully petitioned Baton Rouge’s city council in February 1953, passing Ordinance 222. The ordinance allowed buses to be filled on a first-come-first-served basis, meaning black passengers were allowed to sit in seats previously reserved for white riders.

To the black community’s dismay, many bus drivers and white passengers ignored the ordinance. Several drivers continued to reserve front seats for white passengers and black passengers were mistreated for attempting to sit in “white-only” seats. Bus drivers held a strike and openly voiced their outrage about Ordinance 222, catching the attention of the Attorney General, who eventually ruled the ordinance as illegal. Baton Rouge’s Ordinance 222 did not align with the state of Louisiana’s policy on racial segregation, meaning the city couldn’t enforce a first-come-first-served seating policy.

So begins the first widely-documented major bus boycott in American history.

Leaders in Baton Rouge’s black community assembled the United Defense League (UDL) and called for a mass boycott of the city’s buses. Rallying local churches and other community organizations, the UDL was able to convince over 90% of the city’s black residents to boycott the bus system. People opted to walk or utilize UDL’s organized “free car lift” system, which was composed of over 70 private cars. After six days and a revenue loss of around $1600 a day by bus companies, the boycott was called off after the city came to a compromise with the UDL.

Ordinance 251 kept a similar policy of bus seats being first-come-first-served but reserved the first two rows of seats for white passengers, while the last two rows were reserved for black passengers. All remaining seats were to be filled with whoever boarded the bus first. Although some UDL members wanted to reject Ordinance 251 and continue a boycott, the majority of UDL’s leaders were satisfied with the compromise for the time being.

The Baton Rouge bus boycott set precedent for future boycotts, garnering the support and attention of famed civil right leader Martin Luther King, Jr. King later became the leader of the Montgomery, Alabama bus boycotts, which began in December of 1955.

Contrary to popular belief, Rosa Parks was not the first woman to be arrested in Montgomery for refusing to give up a bus seat. Claudette Colvin, Susie McDonald, Mary Louise Smith, and Aurelia Browder refused to give up their seat months before the monumental events surrounding Rosa Parks in 1955. These four women eventually became the plaintiffs of groundbreaking 1956 court case Browder vs. Gayle, which challenged and dismantled segregation codes.

Rosa Parks was a highly respected member of the black community in Montgomery, making her arrest the perfect catalyst for starting a boycott and subsequent movement. After her arrest, local black leaders, including Dr. King, organized a planned protest against the city’s buses. The protest was initially planned for one day– December 5, 1955– but was extended for 386 days until desegregation demands were met. The Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) and boycotters used methods such as intricate carpooling systems borrowed from Baton Rouge’s previous successful protest.

Browder vs. Gayle yielded a federal court ruling on June 5, 1956 which found bus segregation to be unconstitutional. The ruling was later affirmed by the Supreme Court in November of the same year, ruling Montgomery’s segregation ordinances on buses unconstitutional. The MIA continued the boycott until Montgomery bus transportation was fully integrated on December 20, 1956, over one year after the boycott began.

In 1960 Boynton v. Virginia was brought to the Supreme Court after a black law student, Bruce Boynton, was arrested in a “whites only” restaurant while traveling via bus across state lines. Boynton’s arrest was found to be in violation of the Interstate Commerce Act, which prohibits the inhibition and monopoly of interstate business, generally pertaining to transportation such as buses and trains. Passenger discrimination was ruled to directly affect interstate commerce by the Supreme Court, which subsequently made it illegal to segregate interstate transportation and transportation facilities. Previous rulings such as Morgan v. Virginia of 1946 provided a basis for the unconstitutionality of transportation segregation but failed to be enforced throughout the country, especially in the south. The Boynton v. Virginia ruling finally caused enforcement of fair bus and train policies for black passengers.

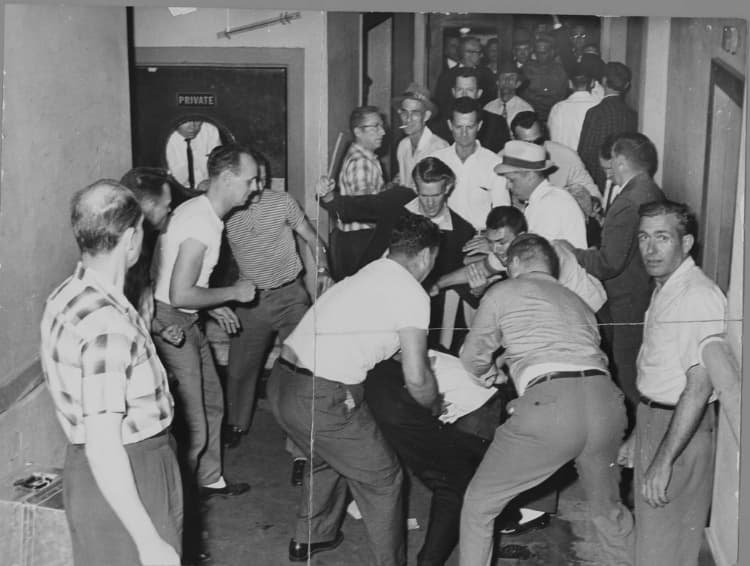

Though segregation on interstate transportation was found unconstitutional, many protestors wondered if Southern segregationists would accept and uphold the new transportation policies. “Freedom Rides” were organized by interracial groups of students in May of 1961, originating in Washington D.C. These students, also known as Freedom Riders, challenged segregationists in the south by riding buses throughout South Carolina, Alabama, Tennessee, and beyond. The Freedom Riders took an oath of nonviolence while traveling, yet encountered horrific violence at the hands of segregationists in the south. Various Freedom Rides were organized throughout 1961, and hundreds of civil rights activists, both black and white, put their lives on the line to challenge social issues beyond transportation segregation.

ADAPT and ADA-Accessible Buses

The history and necessity of ADA-compliant (Americans with Disabilities Act) buses are often overlooked, as modern buses with these accessibility features are commonplace. Not only must public buses be ADA-compliant but charter buses and motorcoach companies must be able to provide an accessible bus upon request.

ADAPT (Americans Disabled for Accessible Public Transit) was an organization that played a vital role in promoting accessibility on public transit. Citizens bound to wheelchairs were neither able to efficiently board city buses nor interstate buses, making it difficult for them to live independently. Members of ADAPT protested the lack of wheelchair accessible buses by blocking routes and laying down in front of vehicles chanting “we will ride!” This was one of the first major political acts organized to garner attention for disabled communities to change the transportation industry.

President Bush signs the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), 1990.

The ADA was introduced into the Senate in 1988, subsequently stalling when it hit the House Committee on Public Works and Transportation in 1990. In March 1990, over 1,000 activists, many of whom had physical disabilities, traveled to Washington D.C. to bring awareness to the stalled ADA proposition. Sixty of these activists decided to forego their wheelchairs and crutches, as they crawled up the steps of the Capitol’s west entrance. This act came to be known as the “Capitol Crawl”, illustrating the struggles and hardship that physically disabled citizens may face. The Capitol Crawl finally pushed the ADA into law on July 26, 1990, with part of the act requiring accessible public and private transportation.

Million Man March: Past and Present

During the pinnacle of the Civil Rights Movement, buses and public transportation were the subject of protest, as well as a way to organize demonstrations for the black community. After decades of movement from segregational practices, buses became a way for the community to continue progression. This includes utilizing buses as a way to transport hundreds of participants for marches intending to focus on unity in the black community. The Million Man March of 1995 was one of the first of such large-scale modern demonstrations.

The Million Man March was organized to take place on the National Mall in Washington D.C. on October 16, 1995. Although the organizers and intentions of the march have been marred with controversy, the overall intention was to promote a different image of the black man in America by promoting family values, guidance, and unity.

The Million Man March in Washington D.C., 1995.

Total attendance to the march has been difficult to accurately measure, with sources ranging from 400,000 to over one million participants. Men from across the country boarded buses to Washington D.C. to participate in this massive event. This even spawned a movie, Get on the Bus, from now-legendary director Spike Lee. The film told the story of a group of men traveling across the country via bus to attend the march. Due to its unprecedented size and goals, the march permanently made its way into American history.

The Million Man March came under fire for sexism and exclusion of black women from the dialogue, which spawned the Million Woman March in Philadelphia the following week. Women rode buses across the nation within the week’s notice to march in celebration and in support of family unity and black women.

In 2015, on the 20th anniversary of The Million Man March, members of the black community took to The National Mall once more for Justice or Else. This anniversary march focused on police brutality and justice for unarmed people of color. The focus of this march also shifted to include white people, women, and other minority groups. Groups chartered buses from across the country, including Cleveland and Philadelphia, to travel to the march.

21st-Century Mobilization of Protests

Each era in America’s history brings along a new generation of activists, focusing on continuously evolving political issues. Although the means of rallying activists has shifted from radio broadcast calls-to-action to the internet and social media methods, group transportation to demonstrations has held the same. Modern mass protests like the Women’s March on Washington have evolved to become complex demonstrations with involvement spanning across dozens of international major cities.

The first Women’s March was organized in January 2017, after the inauguration of controversial president Donald Trump. This march was one of the first mass movements of its kind, focusing on intersectional and inclusive principles ranging from reproductive rights to LGBT+ rights and immigrant rights. Women of diverse backgrounds mobilized across the nation to attend the Women’s March on Washington and sister marches throughout the world. Protestors shuttled to Washington D.C. in chartered buses from across the nation, including from Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Michigan, and beyond.

Charter buses provided a space for women to travel in solidarity from across the world, in order to come together and push back against ideas that affected millions of citizens. To put things into perspective, the District Department of Transportation in D.C. had their work cut out for them during the 2017 march. Approximately 450 charter buses registered for parking permits for Trump’s inauguration. Around 1,800 charter buses were registered for the day of the 2017 Women’s March.

The Washington Post conducted an analysis of international reporting on marches across the world, concluding that around 650 marches occurred throughout the U.S., with international marches bringing the total up to 915. The estimated total of marchers in the US ranged from 3 million to 5.2 million people with an estimated 500,000 to 725,000 of these protestors located in Washington D.C. alone, making it the largest single-day demonstration in history.

Following the first Women’s March in 2017, March for Our Lives in 2018 was one of the most recent political movements spearheaded by young people following the tragic Stoneman Douglas High School shooting. The ongoing battle for gun control reached a pinnacle as hundreds of thousands of protestors took to the streets on March 24, 2018. Young people and supporters organized charter bus transportation to shuttle protestors to D.C. from cities like Baltimore, Atlanta, and Chicago. With the main protest occurring in Washington D.C. and around 800 sibling marches across the nation, March for Our Lives became one of the largest assemblies to date, estimating 1 million to 2.2 million participants nationally.

GOGO Charters has expressed overwhelming support for these modern political movements, providing donations to organizations affiliated with March for Our Lives and the Women’s March. We hope to continue supporting marginalized groups in their efforts to create a change in the world by helping them easily mobilize their movement.

Curious to know about how buses have made an impact throughout history? Check out GOGO Charter’s other deep-dives, like the history of buses in public transportation and the history of bus wraps in advertising.

Recent Posts

- GOGO Charters Expands to the Midwest: Bringing Luxury Intercity Travel to Chicago and Beyond

- Texans Are All Aboard: The Overwhelming Response to GOGO Charters’ New Line Runs

- GOGO Charters Launches Texas-Wide Luxury Line Run Network: Redefining Regional Travel

- Your Charter Bus Packing and Carry-On Guide

- Average Vacation Costs in 2024: Transportation, Entertainment, and Budgeting Tips

- 20 Best Multigenerational Travel Destinations in the U.S.

- 88 Must-Know Travel Statistics by Age Group for 2024

- Top 25 Affordable Warm Weather Destinations in the U.S. for Winter Travel

Do you need to rent a charter bus?

Do you need a long-term shuttle service?

We offer contracted shuttle services for businesses, schools, hotels, and more. Contact our experts at 1-844-897-5201 to discuss your long-term transportation plans.

Overall Rating: 9.98 out of 10 from 422 unique reviews